Published: 2023-08-30 | 8 min read

- ML & AI

- LLMs

- Classification

- OpenAI

- GPT3

- GPT3.5

- GPT4

- Fine-tuning

- Python

Fine-tuned GPT3 still (narrowly) beats generic GPT3.5 and GPT4 models in classification

Disclaimers:

- This was my first time working with Large Language Models (LLMs) and ML & AI in general, so the approach and methodology is definitely far from optimal

- This was a quick exploration and it was also the first time I’ve touched Python in ~2-3 years, so the code is pretty messy

1. Background

On Deck is a curated community designed to increase founders’ odds of building a successful venture-backed company. Community members (fellows) get access to On Deck’s online Community Platform and Slack workspace.

In our community Slack workspaces, ask channels were by far the most popular public channels and we’ve had over 10,000 asks posted, with the vast majority of them getting valuable answers. Fellows have consistently rated asks as one of the most valuable pieces of their On Deck experience.

However, since asks lived in Slack, they could not live up to their full potential

- Asks were completely unstructured so users needed to monitor all posts in the channel

- We were not able to efficiently route relevant asks to potential responders

- Finding existing asks and responses was difficult in Slack

In late 2022, we’ve decided to finally productize asks and bring them to the Community Platform. In order to ensure that we retain all the historical asks, we wanted to import them into the Community Platform. The first important step to enable that was classifying the existing asks. This allowed us to:

- Get a better understanding of the ask usage patterns, which would inform our product and design thinking when building asks on the Community Platform

- Generate structured data for each ask in order to enable better search, filtering, discovery and recommendations

2. Categories and classes

We wanted to pick categories and classes that were most common among fellows and to align them reasonably well with the existing data we’ve had on our fellows, such as their objectives, industries and functional areas.

We’ve settled on the following categories and classes

answer_type_requested(4 classes), i.e.information,connection,favourobjectives(15 classes), i.e.building a product,finding a new role,tools and service providers,finding and validating customersindustries(49 classes), i.e.Marketplace,Insurance,Social,Finance / FinTech,AI / ML,Gamingfunctional_areas(22 classes), i.e.Software Engineering,Marketing,Sales / Business Development,Product Management

Each category also had unknown / other class to capture those that didn’t fall into existing ones.

3. Manual labeling

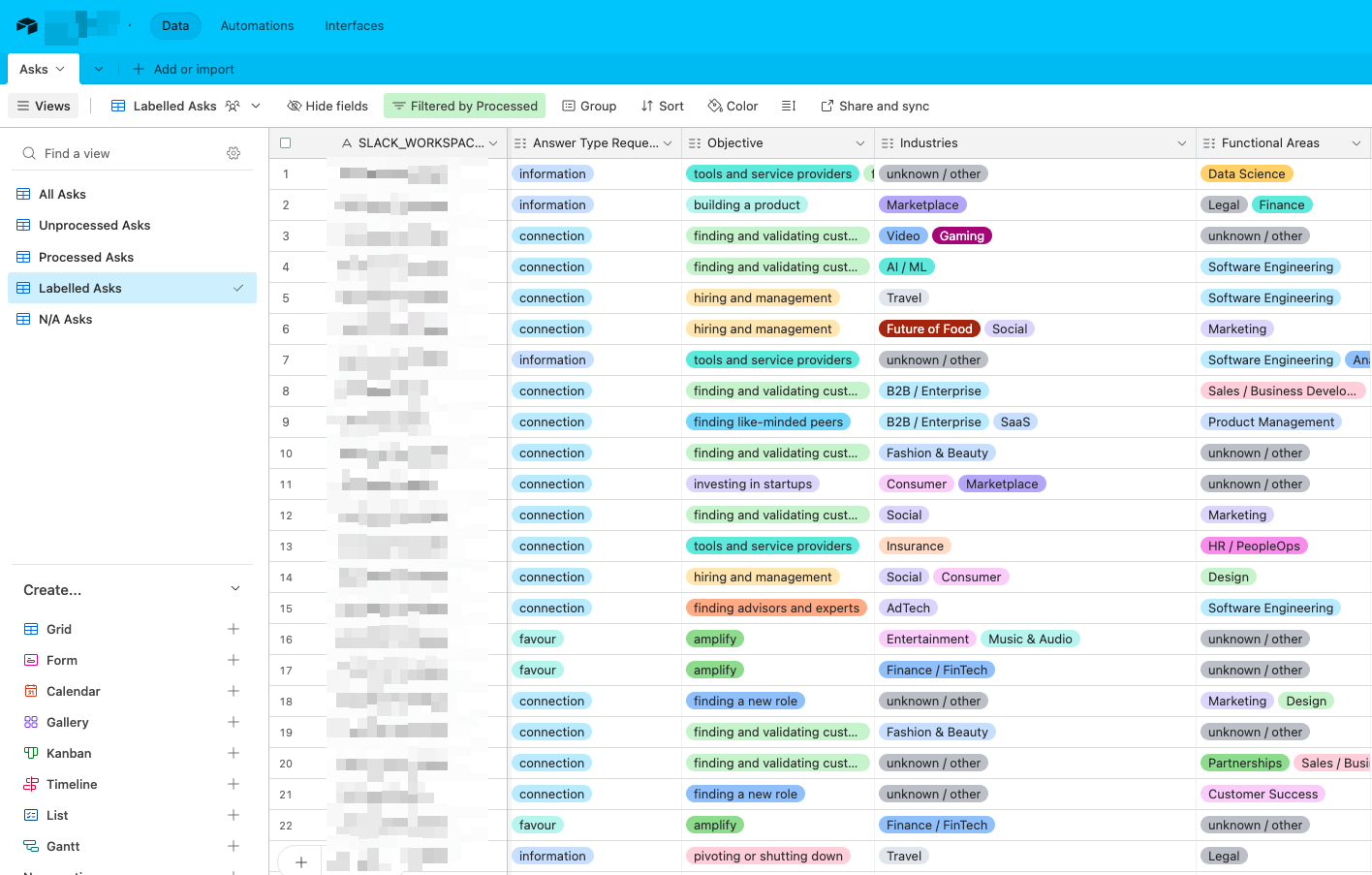

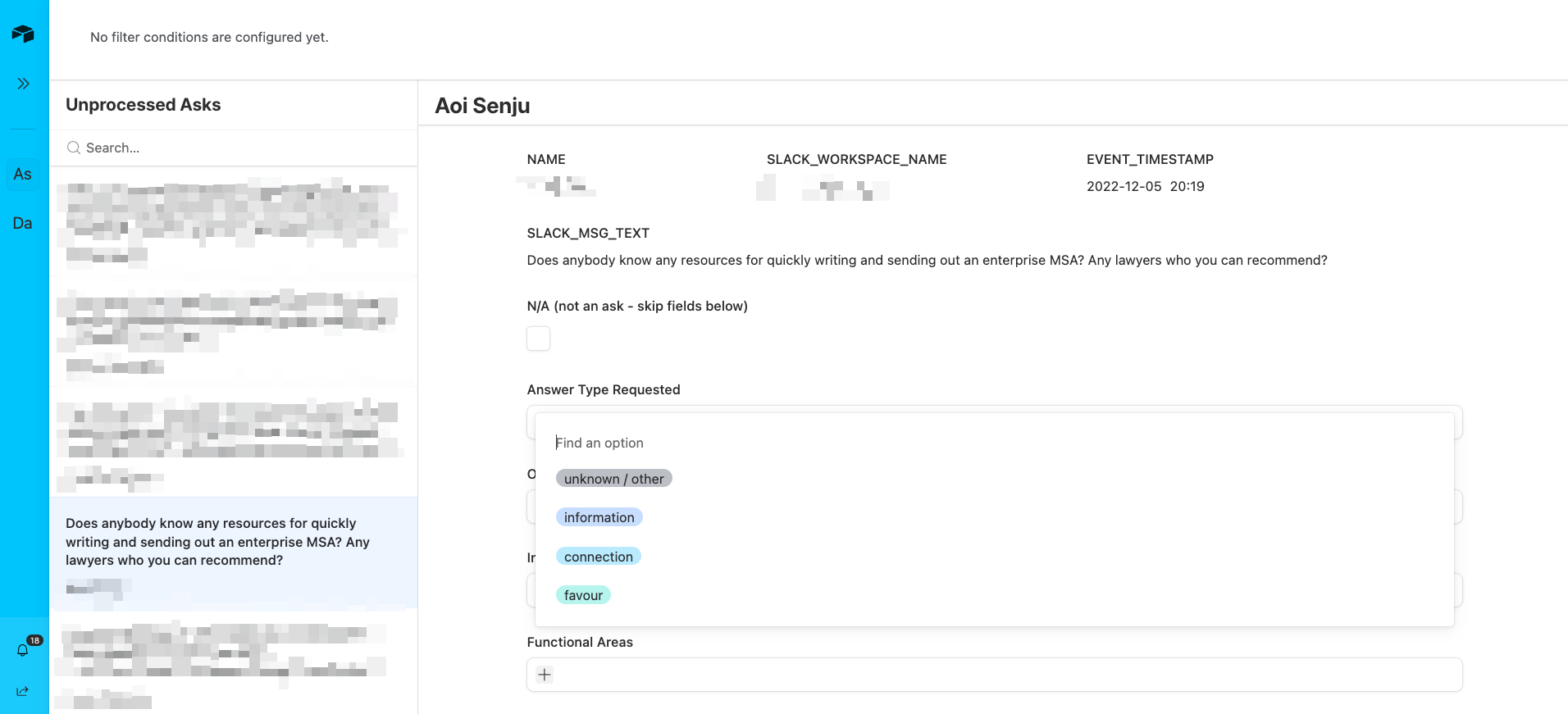

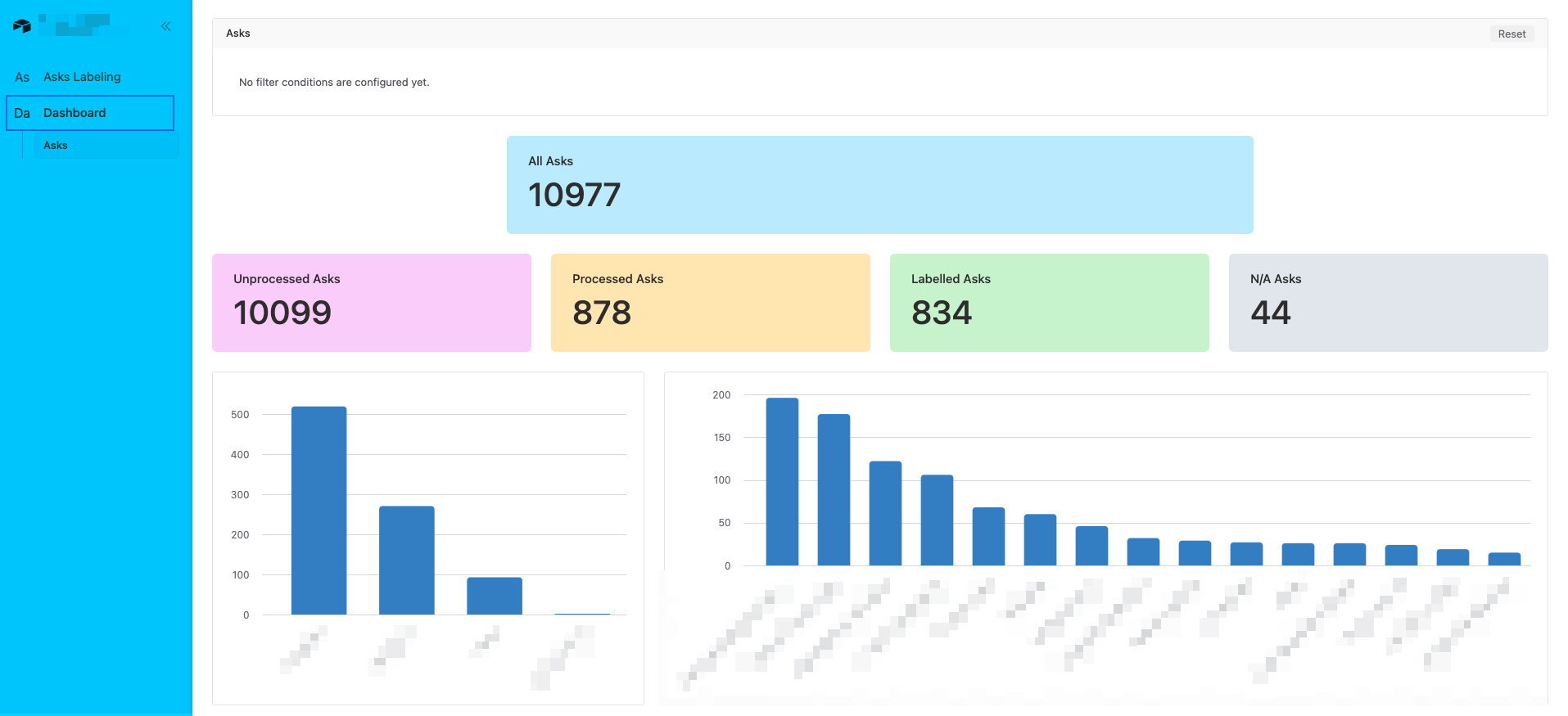

In order to start evaluating potential ML and AI approaches to classification, we needed to have a sample of training and validation data. We’ve created a dedicated Airtable base and imported all the asks there and set up an interface with all the unprocessed asks, where we could review the asks and manually label them across the defined categories and classes.

Imported asks stored in an Airtable

Labeling interface

Simple dashboard

This was a pretty time consuming process but once we’ve gather a sample close to ~100 of examples per class in the first category (answer_type_requested), we were ready to start first evaluations.

4. Evaluating fine-tuned GPT3 models

Since this was end of 2022 and the first time we were working with ML and AI models, we’ve decided to keep things simple and focus on OpenAI’s GPT3 models, which were easily accessible and possible to fine-tune via API. This was likely not the best approach, considering there were a lot of other models that were better for classification purposes (i.e. see Hugging Face - Text Classification Models). However, most of these would require some infrastructure and deployment setup, and we didn’t want to deal with this at this stage.

Fine tuning based on OpenAI (legacy) classification docs was a fairly straightforward in a Google Colab Notebook on a free tier. All you need to feed into the fine-tuning job is a JSONL file with objects consisting of prompt (which should end with a common pattern, in my case \\nAnswer Type Requested: and completion (prefixed with a space).

{

"prompt": "For those of you who have found a technical co-founder, how did you go about doing it? What worked? What didn't?\\nAnswer Type Requested:",

"completion": " information"

}👨💻 See Jupyter Notebook answer_type_requested_singlelabel on GitHub

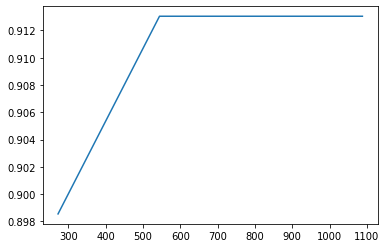

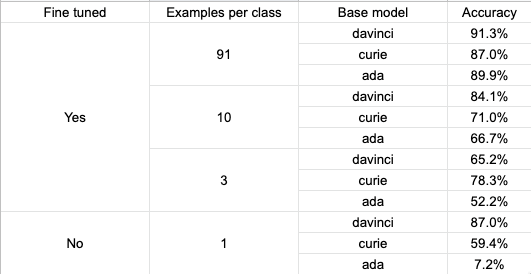

The initial results were quite promising, reaching ~91% accuracy with the davinci model and ~90 examples per class.

However, we also wanted to evaluate other variations of the GPT3 model, as well as different numbers of examples per class. Manual labeling was definitely the most time consuming aspect of this project so reducing the required number of samples would enable us to move a lot quicker.

We repeated the steps above for the other GPT3 models (ada and curie - we’ve skipped babbage after some initial tests as results were very similar to curie).

We were keen to also test the single shot approach, which wouldn’t require any fine tuning, and we would simply provide an example for each class in the prompt.

one_shot_model = 'text-davinci-003'

one_shot_prompt = '''You are a data expert working for a company that supports startup founders.

You are analysing all asks posted on their online forum and classifying them into one of three categories that define what type of answer was requested.

The three categories are: connection, favour, information.

Here are some examples:

ask: I'm looking to speak with someone that could advise us on the way to structure our next fundraising round. Any introductions would be appreciated!

category: connection

ask: We just launched on Product Hunt - would appreciate if you could upvote us!

category: favour

ask: What kind of slides would you include in a pre-seed pitch deck? Any great examples you could share?

category: information

ask: ASK_PROMPT

category:'''The results were quite interesting but also not consistent

- The strongest generic model

davinciperformed very well without fine-tuning, reaching accuracy close to that of the fine-tuned model with the highest number of examples per class - There was a significant difference in accuracy depending on the number of examples per class in fine-tuned models

- The difference in accuracy between different models was significantly smaller with the higher number of examples per class and was very small after fine-tuning with ~90 examples per class

Since we wanted to expand this methodology to other categories, which had significantly higher number of classes, we decided to focus on fine-tuning the davinci model with 10+ examples per class.

A one shot approach with the number of classes going up to almost 50 might not be optimal due to token limitations, and would also make inference quite costly, since we’d need to send all the examples in every prompt.

5. Multi-label classification

For the initial tests, we’ve focused on single-label classification, so we’ve removed from our data set the examples that had more than one class per category for a given asks. However, especially with other categories (objectives, industries and functional_areas) it was critical to support multiple labels per category for a given ask.

Therefore, we’ve explore a couple of potential approaches to this, as OpenAI didn’t have any recommendations on how to handle multi-label classification.

5.1 Single-token completion with logprob evaluation

This approach was inspired by this post by Alex Browne. Here are the steps we followed

- Map actual labels to single token labels from

0ton-1 - Split each row in training sample with a multi-label completion into separate rows with single-label completions

- Inspect

top_logprobs(max 5) in completion response and convert logprob values to percentage probabilities - Set a threshold (i.e. 20%) and include all labels above this threshold as a modified completion (this is a very arbitrary threshold and better methodologies ceratinly exist)

- Compare manual completions with modified completions - very simplified method

- if single label in validation sample completion - 0% or 100% (if label exists)

- if multiple labels in validation sample completion - assign percentage accuracy proportionally to number of labels in validation sample completion, i.e. if 1 out of 3 labels found, assign 33%

- not deducting for false positives

👨💻 See Jupyter Notebook answer_type_requested_multilabel on GitHub

It’s worth noting that this approach is currently only feasible with GPT3 models but it looks like they might also be coming to GPT3.5 and GPT4 eventually.

5.2 Multi-token completion

This approach was inspired by OpenAI docs and the entity extraction example. Here are the steps we followed

- Convert multi-label completions by separating with

\nand ending withEND - Allow multiple tokens per completion and set

ENDas ending - Compare manual completions with completion responses - very simplified method (same as above)

👨💻 See Jupyter Notebook answer_type_requested_multilabel_multitoken on GitHub

5.3 Single-token completion with response probabilities vs multi-token completion

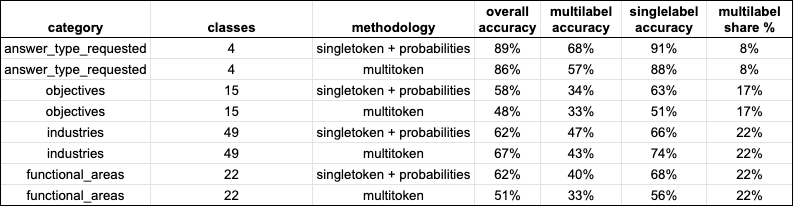

Our tests have resulted in the following insights

- There is a considerable drop in accuracy (relative 25-40%) whenever multiple labels are present in the validation sample completion - the greater the number of classes per category, the greater the drop. This is certainly expected.

- The approach #1 (single-token completion + response probabilities) appears to perform better than approach #2 (multi-token completion) but

- this is based on a rather basic methodology

- it results in a larger number of false positives than in approach #2 (for which we were not penalizing) - this was acceptable in our use case

5.4 Number of classes per category

Another clear insight, which is also expected, is that the number of classes per category has significant impact on accuracy.

answer_type_requestedhas 4 classes and we were able to achieve 85-90% accuracy- Other categories (

objectives,industriesandfunctional_areas) have from 15-49 classes and the accuracy hovers around 58-62%, and is only slightly higher if you exclude the validation samples with multi-label completions)

This delta in accuracy is likely due to

- the absolute number of classes per category (which also amplifies some ambiguities in class definitions and inconsistencies in manual training/validation sample labeling)

- the relationship between number of classes and training examples

- ambiguity around certain categories (i.e. overlaps - can be addressed by merging categories)

- limited ability of the models to understand directionality of labels, i.e.

finding a new rolevshiring and management

ℹ️ Figures above are based on ada model with 10+ examples per class - small, single digit percentage point improvements are possible with davinci model

6. Comparing classification with fine-tuned vs one-shot and GPT3 vs GPT3.5 vs GPT4 models

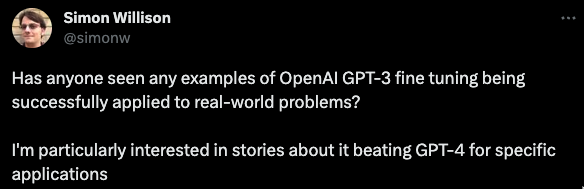

I’ve finally gotten around to turning my notes into this post prompted by a tweet from Simon Willison.

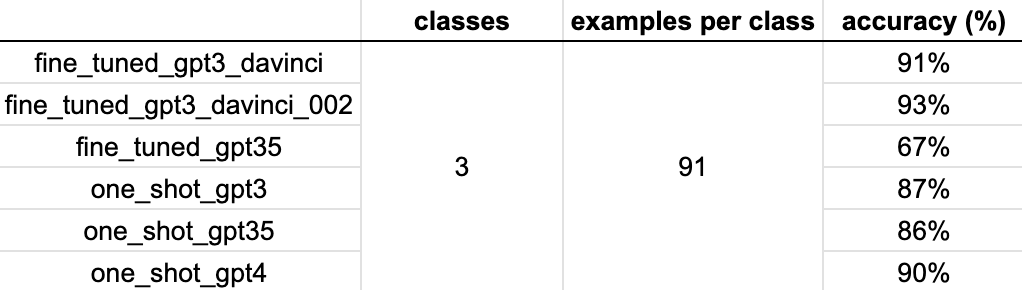

I was curious to compare the currently available fine-tuned GPT3 and GPT3.5 models against generic GPT3.5 and GPT4 models and single shot completions. Since the newer models don’t provide logprobs, I decided to make a simple comparison using answer_type_requested and single-label validation sample with ~90 examples per class.

One adjustment I had to make for GPT3.5 and GPT4 was changing the structure of fine-tuning training data since those models are available via chat completion APIs.

{

"messages": [

{

"role": "user",

"content": "For those of you who have found a technical co-founder, how did you go about doing it? What worked? What didn't?\\nAnswer Type Requested:"

},

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": " information"

}

]

}

The fine-tuned GPT3 models (davinci and davinci-002) still performed slightly better than generic GPT3.5 and GPT4 models with one shot completions. However, the difference was rather small.

Since inference on fine-tuned models is currently 8x more expensive than on generic models (though this is at least partly offset by prompt size due to examples being provided on each inference), and the context window keeps growing, I’d likely lean towards defaulting to generic models and testing their limits with higher numbers of classes. However, even if the context window limit is not a blocker, the speed of inference could still then be an issue though, if you have to send ~15-50 examples in one-shot classification on a generic model.

Interestingly, the fine-tuned GPT3.5 model performed very poorly as it resulted in a lot of completions that were outside of the pre-defined classes.

7. Discussion

The results of this experiment were good enough for us to use the fine-tuned models in production. We’ve classified the remaining ~10,000 asks using the multi-label models based on davinci and single-token completion with response probabilities. We were comfortable with the accuracy of ~90% for answer_type_requested and ~60-70% for the other 3 categories that had a lot more classes. Our use case was to enable better search, discovery and recommendations of existing asks and for that purpose we’ve felt it was sufficient.

More importantly, this was a very useful exercise to understand the capabilities and limitations of GPT3 and LLMs in general, while helping to inspire some other use cases.

7.1 Limitations

- The methodology we adopted was pretty basic and the measurements of accuracy could be improved significantly, and should ideally also penalize false positive

- It would be interesting to compare the results with other models that have been trained with multi-label classification in mind

- Classification across a large number of classes per category is quite challenging and likely requires a lot more examples per class to reach ~90% accuracy, especially in multi-label context

7.2 Classification vs semantic search

While we started productizing asks by exploring classification, we’ve quickly shifted our attention to semantic search, enabled through the GPT3 embeddings, which have improved performance and dropped their price significantly shortly after.

Semantic search partly reduces the need for having structured data, as the historical asks could be discovered by users through unstructured search queries. This works very well for search use cases, however, the classification was still useful to enable filtering, discovery and potential targeting. The classification models could also be adopted to proactively recommend tags during the ask posting experience.

However, the effort in implementing semantic search would be considerably lower as it doesn’t require any manual labeling.

8. Conclusion

Based on these learnings, in similar contexts, I’d recommend

- Defaulting to semantic search first

- Exploring classification if there’s a clear need for it

- Starting by testing the limits of generic models with one example per class

- Adopting fine-tuning (

davinci-002for now) only in case of limitations of a generic model (low accuracy, context window limit, speed or cost of inference)